Between the years of 1860-1920, approximately 400,000 migrants left the Ottoman Empire for the United States. Whereas US Census data refers to all persons from the Ottoman Empire simply as “Turks,” this group was incredibly diverse, including Syrian, Lebanese and Palestinian Arabs, Greeks, Armenians, Sephardi Jews, Kurds, Macedonians, Albanians, and others.

While sizable diasporic communities formed first in the major East Coast cities of New York, Boston, and Washington D.C., a number of migrants also made their way westward to cities such as Detroit.

As early as 1903 the Detroit Free Press reported on the growing “Syrian Colony” in the “City of the Straights.”

With a population of approximately 200, the article notes, Syrians had already set up shops on Woodward and Gratiot Avenues, as well as a drygood establishment on East Atwater Street.

Around this same time, growing numbers of Armenians and Turks from the Harput/Kharpert region of the Ottoman Empire also began migrating to the United States. Many sought work in Detroit, with migration peaking around Ford’s 1914 promise of $5-a-day jobs. By 1922, upwards of 1,500 Armenians and 1,500 Ottoman Turks, Kurds, and Syrians were living in and around the city.

Just as Ford’s records reveal the diversity of its workforce—letters, travelogs, poems, newspapers, songbooks, photographs, and countless other documents from this time period point to the profoundly multiethnic and multilingual milieu in turn of the century Detroit.

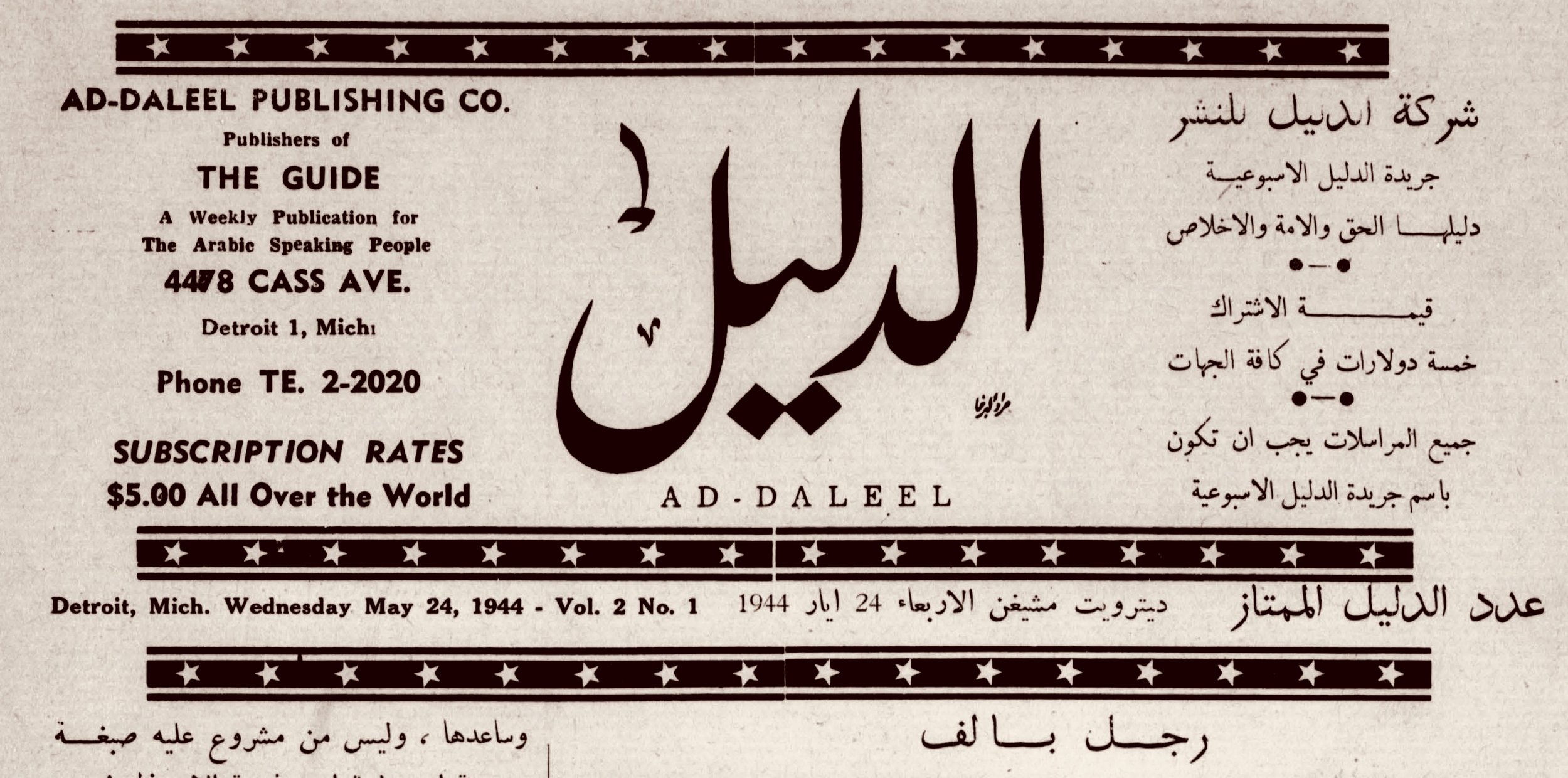

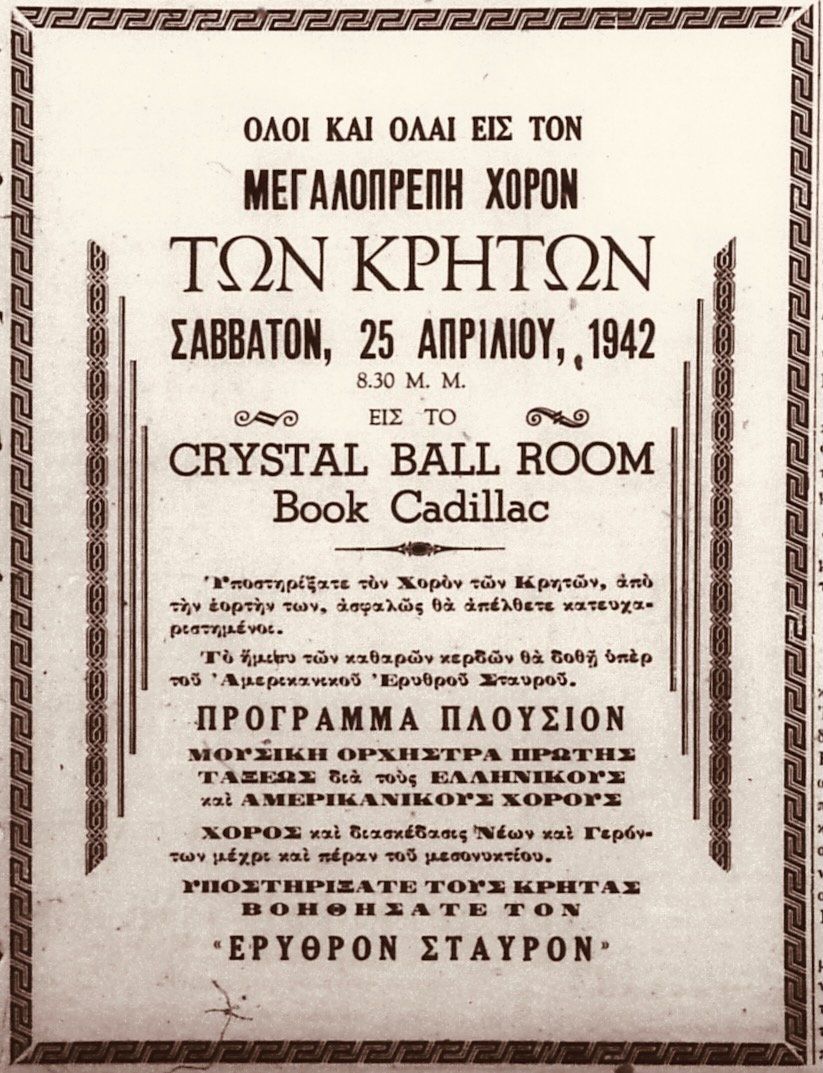

As migrants navigated their new worlds in Detroit through a mixture of languages, they also translated the city into a multilingual panoply.

Texts and images produced in this time period express a longing for home while also laying claim to the city of Detroit. They combine classic American iconography with expressions of cultural tradition. And they subtly mark the boundaries of individual migrant communities while belying the myriad interconnections between them.

Focusing on roughly the first half of the 20th century, The Middle East in Metro Detroit renders precisely such contradictions and connections visible. Approaching the “Middle East” in a capacious way, we focus on diverse peoples from former Ottoman territories, including groups that engaged with and included themselves in “Middle Eastern” fashion, such as Greek nightclub owners who utilized Middle Eastern iconography in their advertising and hosted musicians of different ethnicities in their evening performances.

What brought these different communities together and what drove them apart? Even as migrants may have harbored ingrained prejudices against one another, in what ways did they collaborate in their new homeland?

How do the tensions and synergies between different migrant groups from the (former) Ottoman Empire help us to see Detroit from new angles, as both a dynamic and contested site of multilingual contact?

The Middle East in Metro Detroit explores these questions and others through a series of story maps and long-form translations published on an ongoing basis, which incorporate texts in a variety of languages. Focusing on themes such as Coffeehouses and Nightlife, Work, Worship, and Publishing and Advertising, these materials open up different avenues through which to explore the complexities of migration to the city.

Above all, the stories and translations presented here attest to the rich cultural contributions of immigrant communities to Detroit and its surrounding neighborhoods, and the many ways that migration has been central to the formation of Detroit’s identity since at least the early 20th century.

Take themed tours of Metro Detroit through archival images and multilingual primary sources, presented here in their original languages and in translation:

The Middle East in Metro Detroit is directed by Kristin Dickinson and Michael Pifer.

As a fundamentally multilingual endeavor, this project has benefited greatly from the additional research, editorial assistance, translations, and personal reflections provided by Fatima Alhawary, Emma Avagyan, Dikran Callan, Gottfried Hagen, Hachig Kazarian, Harry Kezelian, Marina Mayorski, Devi Mays, Ammar Owaineh, Vahe Sahakyan, David Soffa, Ronald Stockton, Will Stroebel, Berkay Uluç, Veronica Williamson, Kyle Wynter-Stoner, and Ernest Zachary.

The followıng institutions have generously provided archival materials and/or research assistance: The Arab American National Museum, St John Armenian Church, Edward and Helen Mardigian Library, Hellenic Museum of Michigan, Wayne State University, Center for Armenian Studies (U-M, Ann Arbor), the Armenian Research Center (U-M, Dearborn), and the Bentley Historical Library (U-M, Ann Arbor).

This project has received generous funding from the Provost’s Office at the University of Michigan and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the Provost’s Office or the NEH.